Lectionary Week 10, Desertide 9

Confessional Readings

Of Christ the Mediator

Westminster Confession of Faith 8

Belgic Confession of Faith 10, 26

Canons of Dort II Rej. 2, III/IV.12

Heidelberg Catechism 14-18, 35

Old Covenant Readings

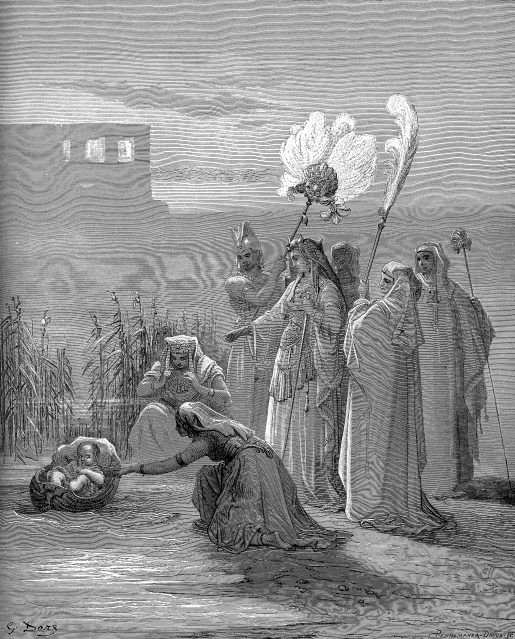

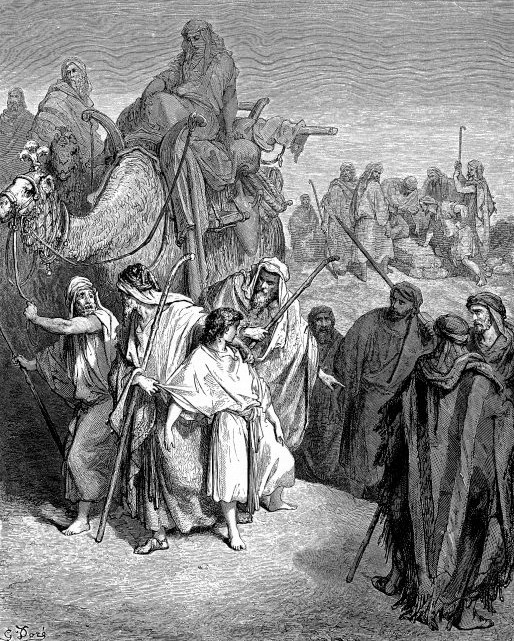

Exodus 1-6

New Covenant Readings

Revelation 17-22

Psalms

(Of David) 63-70

Overview of Exodus

Author, Date. Moses probably wrote the legal portions of the book (i.e., chs. 20-31) shortly after the Exodus in 1446 BC and the narrative portions in as part of the overarching Pentateuchal narrative closer to the end of the Wilderness period in 1406 BC. Moses wrote that he received the moral law from the “finger of God” at Mount Sinai (Exod. 31:18, Deut. 9:10). The complexity of the civil and ceremonial laws would have necessitated writing them down so they could have given guidance to the people. The narrative account indicates Moses wrote the words of the LORD while he was still on Mount Sinai in the presence of the LORD (Exod. 24:4).

Many modern critical scholars deny the historicity of Exodus, assuming that the Pentateuch was written hundreds of years after the fact. Such an assumption, however, is driven by an a priori denial of the truth of the supernatural nature of the events surrounding the Exodus. In contrast, Scripture posits the Exodus as a historical reality. In support of this, what is obvious but should nevertheless be noted is that from Exodus through the remainder of the Pentateuch, Moses writes as an eyewitness—indeed, as the primary eyewitness—to the events recorded. This underpins the authority of the account and gives it narrative coherence. Also, Moses and God’s people are often described in an unflattering, even negative manner, in Exodus, an approach which radically differs from the hagiographic manner typically taken in the contemporary chronicles of surrounding nations; this actually reinforces the truthfulness of Exodus.

Covenantal Significance. The Exodus is the paradigmatic salvation event of the Old Testament. It is paralleled in the New Testament only by the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ Jesus in the New Testament, which is presented as a recapitulated Exodus, especially in Matthew’s Gospel. The Book of Exodus also gives the moral, civil, and ceremonial law as the core of the Sinaitic covenant. In understanding the law and its relationship to God’s grace, it is important to keep in mind that God gave the law after He had already saved His people. Thus, the law was never meant as a means for achieving salvation; rather, it was meant to train God’s people in understanding the righteousness required of them as God’s people reflecting God’s image (see Gal. 3:24-25). As the civil and ceremonial laws were tied specifically to the functioning of theocratic Israel in the particular circumstances of its time, with the dissolution of that state those laws are no longer in effect, although they continue to have merit for Christians in terms of articulating enduring principles of general equity and holiness.

Outline. There are three major sections to the Exodus narrative: (1) the Great Deliverance of the Exodus itself (chs. 1-18); (2) the Sinaitic Covenant (chs. 19-31); and (3) Israel’s breach of the Covenant in the Golden Calf incident and its subsequent restoration as a result of the mediation of Moses. The book ends with the dwelling of God in the Tabernacle, a fulfillment of God’s promise to be with His people now that He has saved them.