When you go near a city to fight against it, then proclaim an offer of peace to it. And it shall be that if they accept your offer of peace, and open to you, then all the people who are found in it shall be placed under tribute to you, and serve you. Now if the city will not make peace with you, but makes war against you, then you shall besiege it. And when the LORD your God delivers it into your hands, you shall strike every male in it with the edge of the sword. But the women, the little ones, the livestock, and all that is in the city, all its spoil, you shall plunder for yourself; and you shall eat the enemies’ plunder which the LORD your God gives you. Thus you shall do to all the cities which are very far from you, which are not of the cities of these nations. But of the cities of these peoples which the LORD your God gives you as an inheritance, you shall let nothing that breathes remain alive, but you shall utterly destroy them: the Hittite and the Amorite and the Canaanite and the Perizzite and the Hivite and the Jebusite, just as the LORD your God has commanded you, lest they teach you to do according to all their abominations which they have done for their gods, and you sin against the LORD your God. (Deuteronomy 20:10-18 NKJV)

What are we to make of this?

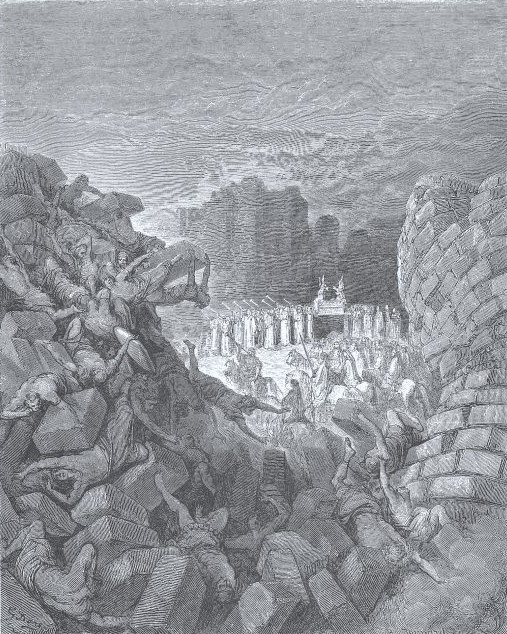

On the face of it, what the Lord is commanding the Israelites to do to inhabitants of the Canaan is in modern terms ethnic cleansing (that is, removing an entire people group from their land) and genocide (destroying an entire people simply because they belong to that group). Even the more “benign” treatment of captured cities outside of Canaan gives some pause in light of the Lord’s command to put all the men of the captured city to death. Nor is this the only passage describing such violence. In the account of the Flood (Genesis chapters 6-8) the Lord destroys the entire world for the depravity in it, save Noah’s family. He disperses the nations of the world in response to the hubris of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11, completely destroys the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis chapters 18 and 19, and leaves Egypt in ruins as a result of the plagues that led up to the Exodus of the Israelites (see Ex. 10:7). In Exodus 23:20-33, He tells the Israelites that His Angel will completely destroy the people groups later repeated in Deuteronomy 20 so that Israel can occupy the land and that these peoples will not be a snare to them. The law codes of Exodus and Leviticus are probably the earliest parts of Scripture, so this means that these statements go back to the earliest part of the biblical history. In Numbers 33:50-56, these commands are repeated again on the plains of Moab, as Israel is planning to enter into the land which the Lord has promised. Leading up to that point, in the precursor to what the Israelites would later do in Canaan, the “Lord’s vengeance was executed” on Midian and the Israelites killed all the men. When Moses and Eleazar the high priest learned that women and children had been spared, they became angry and ordered the wives and male children of the Midianites to be killed as well (Num. 31:17).

Clearly there is a pattern here.

The critic of the Faith will point to these passages as prima facie evidence for the idea that if they are true and if God exists at all then He is neither good nor loving. Conversely, such commands for violence seem to be utterly incompatible with both modern sensibilities and modern expectations of the benign character of Deity and seemingly can only mean that if God really exists then Scripture is not true. And if Scripture is not wholly true, then that raises the obvious question as to what parts are true and what parts are untrue and on what grounds does one decide? It is not hard to see in light of those questions that it is a short road from rejecting difficult parts of Scripture such as these to a more fundamental questioning of the Faith. Thus, these holy war passages are not an easy question for Christians to face. For the Christian, the passages go beyond the idea that the Lord permits evil to happen. They seem to say the Lord is active in doing injustice and this puts God on the same level as Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, Pol Pot, Jean Kambanda,[1] Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Milosevic, which is an unpalatable conclusion. That returns us to the earlier question of what we are to make of these passages.

No Dichotomy and No Easy Way Out

The natural inclination for many Christians is to posit some kind dichotomy between Jesus on the one hand and the passages of divine destruction in the Old Testament. In this way, Jesus trumps the commands on warfare and they can be conveniently ignored. Thus, some argue that these Old Testament passages reflect an early stage in Israel’s evolution which Jesus later superseded with His teaching on love and turning the other cheek. The problem with this is that Scripture itself shows the Israelites were not as “primitive” as they are made out to be by this caricature. The “primitive” Israelites had no stomach for the bloodiness of the holy war commands and they actually cut deals with their pagan Canaanite enemies rather than exterminate them as the Lord commanded.

A variant of this is the idea that the Old Testament depicts the Lord as a God of wrath, whereas the New Testament reveals Him to really be a God of love. This is simplistic and unsatisfactory, especially if one intends to take Scripture seriously. Jesus, who talked about turning the other cheek in the Sermon on the Mount, said in the same sermon He did not come to abolish the Law but to fulfill it (Matt. 5:17). His descriptions of Hell and of the pending Final Judgment—more frequent than that by anyone else in the New Testament (see Matt. 5:22-30, 10:28, 18:9, 23:15 & 33)—show that the wrath of God is not limited to the Old Testament alone. Indeed, Jesus’ own death on the cross to propitiate God’s wrath is sufficient evidence of that.

On the other hand, love and mercy are not the exclusive monopoly of the New Testament. When the Lord put Moses in a cleft of a rock, passed by, and declared His name he described Himself as “merciful and gracious, longsuffering, and abounding in goodness and truth; keeping mercy for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, by no means clearing the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children’s children to the third and fourth generation” (Ex. 34:6-7). When Jesus was asked about the greatest commandment in the Law (Matt. 22:36), He quoted the Old Testament to show the Law was summed up in the command to love the Lord with all one’s heart, soul, and mind and to love one’s neighbor as oneself (Deut. 6:5, Lev. 19:18). Again, this does not easily fit the stereotype of the Old Testament being of law and judgment and the New Testament being one of grace and forgiveness. It is fair to say that the Lord is depicted as both loving and judging in the Old and New Testaments.

The greatest challenge to positing a dichotomy between Jesus and these commands on holy war is how Scripture actually links the two. The Apostle Luke records two of Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances and in them Christ gives His disciples insight into how Scripture is to be understood. In both cases He says that all Scripture points to Himself (Luke 24:27, 44-45). This, of course, must also include the holy war passages of the Old Testament as well. Indeed, in the Ex. 23:20-33 passage mentioned earlier, the Lord tells Moses that He will send an Angel ahead of the Israelites to bring them into the Promised Land and defeat their enemies. Although the identity of the Angel is not conclusive for scholars, He most likely is the pre-incarnate Christ. The Lord, for example, says that this “Angel” is to be completely obeyed because God’s name is “in Him.” Christ bears God’s name and, moreover, the Lord and the Angel are used interchangeably through the passage. Joshua later encounters what is probably this same Person before the conquest of Jericho when he meets the Captain of the Lord’s army. That this Captain is the pre-incarnate Christ is evident from the fact that he unhesitatingly accepts Joshua’s immediate response of worship (Jos. 6:13-15). Elsewhere in Scripture, when homage is offered to angels they redirect that to God alone. Not here though. What all this means is that the shocking violence of the holy war passages probably had Christ Himself at the center—the same Christ who taught the Sermon on the Mount which so many pacifists take as their primary proof text. There is no easy way out of the challenges these passages pose.

Confronting the Personality and Power of God

Without question, the holy war passages challenge our presuppositions about who God is. This is evident in the most common reaction people have when they ask, “How could a loving God command these things?” This question, however, makes a presumption about God’s character that first of all needs to be examined more closely. God’s character is only known to us from what He has revealed in His Word. The fullness and complexity of God’s Word should be a curb to the temptation to select a few attributes with which to create a caricature of God whose appropriateness we will then judge. The question, “how could a loving God command these things?” however, tends in the direction of caricature with the fundamental assumption that God’s defining trait is love. Admittedly, John the Apostle says “God is love” in his first epistle (1 John 4:16), and while this is a true statement according to Scripture, the fact of the matter is that God is not reducible to just that trait.

Imagine, for example, describing one’s best friend or spouse solely with the term, “loyal.” It may well be true, and it could even be an exemplary trait in that person. But that term by itself is insufficient to answer questions about what motivates the person, what his likes and dislikes are, what experiences have shaped who he is or what aspirations he may have. People are far more complex than can be summarized by a single personality trait. Why, then, are we so inclined to think that the Lord—who is Three Persons in one Godhead—can be reduced simply to “love”? The effect of this is to make God into a principle, not a Person. This depersonalization makes it easier to write Him off. If God is solely love, then it is not hard to conclude that “Love is god”—indeed, the conclusion follows tautologically. Because there is ambiguity associated with defining what “love” is, it becomes all too easy to dismiss God because He does not match what we assume or want love to be. As a result, for some individuals (certainly not all), the question of “how could a loving God command these things?” may well be a veil for what is really a more fundamental rejection of a judging God.

Yet by what right do we have to judge God? The question “How could a loving God command such things?” is too often merely an intellectual one. The fact of the matter, however, is that if God is the Creator God of the heavens and Earth, then this Being—whatever His character—possesses a power that is well beyond our capabilities. God, for His part, knows our very being to the utmost subatomic particles. He could change the minutest thing to heal us or he could annihilate us completely. This raw power is evident from nature. Whether God is consistent or inconsistent with Himself, whether He is good or evil or whatnot is secondary to the fact that He is omnipotent and can hurt us. God is a reality with whom we need to reckon on a personal level, not an abstraction for a dorm room bull session.

To be sure, this is not to suggest that whatever God does is right simply by virtue of the fact that God does it. God’s actions are consistent with His character, so if justness is part of God’s character (as it indeed is), then God will act justly in accordance with who He is. The only way we can know God’s character is through what He has revealed in His Word. The logical implication of this is that there are no legitimate grounds for dismissing God on the basis of His character if Scripture is not admitted to the discussion. And if Scripture is admitted, then intellectual honesty must concede that the picture of God’s character is richer than cherry picking a few traits would portray. The implication of these points is that we need to approach this topic with sobriety and humility. It is not without reason that Scripture says the “Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” (Ps. 111:10, Job 28:28, Prov. 1:7 and 9:10).

One last note with regard to invoking 1 John 4:16. Although it sounds spiritual to reduce God to “love,” even the Apostle John would not have meant his statement to be taken in this way. This John was the same John who started off as a disciple of John the Baptist. In this, he no doubt shared the Baptist’s expectation of imminent eschatological judgment. Remember, the Baptist called for his hearers to repent because “…even now the axe is laid to the root of the trees…” and judgment is near (Matt. 3:2, 10). This same Apostle John and his brother received the nickname “Boanerges”—sons of thunder (Mark 3:16)—perhaps in part because of an incident recorded in Luke 9:51-56 in which they were prepared to call God’s wrath down on a Samaritan city that had disrespected Jesus. This very John also was the one who penned the Book of Revelation, which features front and center God’s wrath and Final Judgment on the world, executed through Christ Jesus. God’s judgment and God’s love clearly are not antithetical in John’s thinking.

Defending the Covenant Lord’s Image

If it is inappropriate to reduce God to merely being “love,” then perhaps there is a better way of phrasing the concern being raised here, especially for Christians genuinely wondering how to reconcile this with other aspects of God’s character. To that end, one could well ask how it is that God, who imparted dignity to men by making them in His own image and who commanded His people to love their neighbors as themselves, would also command them to engage in a hideous attack on His own image bearers? If God created man in His own image, then God’s love would seem to naturally follow. Yet, the apparent unjustness of the holy war commandments is that they seem so unprovoked and so disproportionate. How could God command this and not contradict His own character as being just?

The issue of God’s image is at the heart of the matter posed by the holy war passages. That said, what it means to have been made in the image of God is something that is poorly understood by most Christians. Some, like Thomas Aquinas, make this a matter of man’s superior intelligence as distinguished from the lower animals. Others, like Martin Luther, make this a matter of man’s moral character. The Westminster Confession of Faith, drawing on Eph. 4:24 and Col. 3:10, captures both of these ideas in noting that man was “endued with knowledge, righteousness, and true holiness, after His [God’s] own image” (WCF IV.ii). There is a richness in the notion of image which goes beyond these qualities, however, and which I would posit is fundamentally covenantal in its orientation.

In ancient Near Eastern covenants, the suzerain king often would not only obligate the vassal king with upholding his political interests, but also with defending his name and honor. For the vassal, this was a way of demonstrating his loyalty to the suzerain. For the suzerain, it was a way of projecting his majesty and authority both within the vassal’s realm and beyond it to those regions not incorporated into the suzerain’s empire. Thus, for the vassal to bear the image of the suzerain was not only something that is intrinsic to the individual, as in many theological formulations, but it is also reflective to the surrounding world. To demonstrate their loyalty, vassal kings would not only swear allegiance to the suzerain, but would often adopt the suzerain’s gods, the suzerain’s governing practices, even the suzerain’s personal styles. Imitation, of course, is the highest form of flattery. One can see a perverted form of this in the Scriptural account of Ahaz’s relationship to the Assyrian Empire in 2 Kings 16:10-18 and 2 Chronicles 28:16-25. There we see Ahaz willingly subordinating himself to the Assyrians in order to gain assistance against local threats. As part of this, he went to Damascus—at that time occupied by the Assyrians—and among other things copied the altars the Assyrians used for worship. Upon returning to Judah, he began instituting worship of Assyrian gods. He did this not only to demonstrate his loyalty to his Assyrian overlords, but because he believed the Assyrian gods were stronger than the Lord.

In the Lord’s relationship with His people, he expects them not only to uphold His name, but to reflect His character. Indeed, this is embedded in the Law that He gave to Israel at Sinai and which was recapitulated forty years later on the plains of Moab. As indicated by the First, Second, and Third Commandments of the Decalogue (Ex. 20:4-7), the Lord jealously defends His name and prerogative. Not only does He refuse to be dishonored, but He determines how He will be honored and is exclusive in demanding His people’s loyalty to Himself. That this is so can be seen in another verse that is often difficult for Christians to grasp, 2 Sam. 12:14. This verse occurs after the prophet Nathan confronts King David over his sin with Bathsheba. Although David repented, Nathan added, “However because by this deed you have given great occasion to the enemies of the Lord to blaspheme, the child also who is born to you shall surely die.” To most readers, this seems unfair. The baby born to Bathsheba did no wrong, so it is not clear why he should have to die for his parents’ sin. Had the child lived, however, the gossipmongers among the court—and eventually the public more broadly—would have been keenly aware of the double standard between David’s professed faith and his actual actions. The natural inclination would have been to consider the faith a charade or God, if He exists, to be impotent or inconsistent. God would not let his Name be sullied like that—not to David’s court, not to the surrounding nations, and not even to the supernatural powers and principalities of this world. What the leader did would in time encourage the people to mimic as well. By causing the child to die, the Lord showed that above all, He would be honored and that he would jealously guard His name.

The Sins of the Canaanites and the Justice of the Lord

The Lord’s intention to defend His name and his image have direct bearing on what He was to do to the Canaanites. In withholding His hand of grace, the Lord allowed them to pursue whatever lifestyle they chose. To say that the worship they chose was depraved does not really provide a clear image to our minds and can be too easily dismissed as mere moralizing. It is therefore worth looking briefly at Canaanite religion and society.

Texts from the ancient Near Eastern city of Ugarit (modern day Syria) provide much insight into Canaanite religion beyond what is mentioned in the Bible. The Canaanite pantheon was headed by a shadowy creator god named El. The more prominent deity, however, was Baal, the storm god who controlled the rains necessary for agriculture. According to the Ugaritic texts, Baal would yearly fight with the god of death, Mot, and lose, ushering in a period corresponding to the agricultural dry season. Fertility would only be restored to the land by the annual sexual intercourse between Baal and Anath. Anath is variously described by scholars as either Baal’s sister or the sister and wife of El and was renown for her vengefulness. Baal’s other sexual consorts were Asherah and Astarte, also described as being both El’s wives and sisters. Like Anath, they were goddesses associated with violence and war. Although the Ugaritic texts do not explicitly state so, it is not hard to infer from them the prevalence of ritual male and female prostitution in the Canaanite religious system. Numerous ancient figurines of nude female figures found throughout the Near East, combined with the foregoing cosmology and contrasting Scriptural prohibitions against such practices suggest that these things were prevalent throughout the region. It is unclear from the Ugaritic texts whether human sacrifice was part of this system, although it most likely was. Because Israel did not completely destroy the Canaanites, there was a persistence of Canaanite practices that were incorporated into the worship of Israel and the surrounding nations. In 2 Kings 3:27, for example, the king of Moab offered his son as a burnt offering. King Ahaz of Judah similarly sacrificed one of his sons (2 Kings 16:1-4), an unidentified brother of the good reformist king Hezekiah. Hezekiah’s son Manasseh also offered human sacrifices of his sons (2 Chron. 33:6).

This cosmology had to have an effect on Canaanite society on the personal and familial level as well. The glorification of violence and the intrigues among the gods of the Canaanite pantheon had their parallel in the fundamental political disunity of Canaan. If the gods were engaged in orgiastic and incestuous sexual practices, then it is not hard to conceive that people would emulate those things. Indeed, it is foregone conclusion that they did so. Incestuous relationships, fornication, and violence were all intertwined with personal advancement. To get ahead in Canaanite society materially one needed the favor of the gods, which meant appeasing their anger (i.e. human sacrifice) and emulating their practices (incest, promiscuity). We know from modern victims of child sexual abuse the lasting psychological traumas resulting from such abuse. The abused, moreover, too often become abusers themselves. We further know from modern sexual mores that, however much permissiveness is tolerated or encouraged by society, jealousies and insecurities abound with such practices on a personal level. Emotional scarring, relational distrust, and familial rivalries resulting from these things literally tear apart families and turn them against themselves. This would only be reinforced by the practice of human sacrifice. It could not have encouraged family harmony to know that if the family fell on tough times then father would sacrifice one of the children to the gods. Nor would it end there. As Israel increasingly adopted syncretistic worship that incorporated these practices, the Lord’s prophets not only condemned them for these things, but for other evils emerged as well. Efforts to get ahead by appeasing or manipulating the gods through such practice no doubt divided society into the haves and have nots, since success was deemed divinely endorsed. Those who did not achieve success earned only contempt and their only recourse was to turn to the same debased practices. This cycle only fostered injustices and oppression in society.

This is the society that the Lord instructed the Israelites to destroy. Such people, though not chosen by Yahweh, bore His image simply by virtue of being human. Their behavior, however, was completely contrary to His character—indeed, it reflected a rejection of everything about who the Lord was and how He worked. For Him to allow that to stand would have been to consider the desecration of His image as acceptable. The Lord will defend His name and His image indeed, especially since He is the True Suzerain. The sin of the Canaanites justified the Lord’s judgment if He was to vindicate His name. The pervasiveness of Canaan’s religious system throughout all of society also explains the command to bring judgment not only on the men, but also on the women and children of the society as well. In our understandable focus on individual responsibility we often forget the strength of social networks. To use modern parlance, the Canaanite religious system was totalitarian. In Canaan, however—unlike, say, Nazi Germany in the twentieth century—this religious system had grown up over centuries rather than being imposed at once. Because of this, it was more organic and thus more resilient in how it was interwoven into the social fabric. For Israel to have spared anyone would have meant that the survivors would be intent on preserving their old ways and gaining revenge for their losses. It is facile to suggest that Israel could have “converted” the survivors to the true faith—indeed, as Scripture shows, Israel did spare some Canaanites, but it was the Israelites, not the Canaanites, who adopted their enemies’ religious practices.

The Lord was indeed just in bringing judgment down on the Canaanites, even as argued here, completely upon the society as a whole. It should be noted, however, that even this is not without certain elements of mercy. In the Exodus account of the holy war commands, God says that He will send a terror ahead of the advancing Israelites to drive out the peoples in Canaan and that the campaigns would be incremental (Ex. 23: 27-30). Israel’s early victories and the likelihood that the inhabitants of Canaan eventually would have gotten wind of God’s command for their total destruction would have established a lasting fear among the inhabitants. Prior to successive battles, this fear, combined with “God’s terror” (e.g. hornets, Ex. 23:28) would have produced a kind of psychological warfare to encourage the Canaanites to flee if they knew the Israelites were coming. In the way that the Lord gave His commands, those who fled to cities outside of Canaan would have been covered by those regulations He gave Israel for how to treat the “faraway” cities; only those who remained would be subject to the command. One sees echoes of this approach in the battles leading up to Israel’s entrance into the Promised Land, as well as in the guile of the Gibeonites (Josh. 9) who fooled the Israelites into thinking they were from a distant city to avert their destruction. Psychological warfare thus could have mitigated the actual number of people killed.

The Lord’s Ultimate Ends in the Destruction of Canaan

The distinction between how Israel was to militarily treat the “faraway cities” vice the cities in Canaan serves to highlight the fact that the total destruction kind of warfare the Lord commanded for Israel in Canaan was not to be the normative practice for Israel for all time. Presumably, if Israel had been fully obedient to the Lord in its conduct of battles in Canaan and all of the inhabitants were killed or driven out, then the only operative warfare regulations would have been those for the “faraway cities”—regulations consistent with customary ancient Near Eastern practices at the time. The destruction of Canaan therefore was unique for that situation. Because the ban on Canaan was unique though, it is important to remember that God’s agenda in this action was not limited to judgment upon Canaan. The Lord, being a personal Being, was pursuing multiple agendas simultaneously.

In using the Israelites as His instrument of judgment on the Canaanites, the Lord also was settling the Israelites into the land He promised to their forefathers. Suzerains in the ancient Near East would often provide loyal vassal kings with land grants as a way of rewarding their past loyalty and to encourage their future loyalty. Failure for the suzerain to follow through on a promised grant could be considered an abrogation of the covenant. As the True Suzerain, the Lord was following through on His promises made originally to Abraham (Gen. 15:18). More than that, however, the Lord was in the process of creating a people for Himself, and the land was emblematic in His people finding their ultimate blessedness in their sovereign Lord. The land was a foreshadowing of the eschatological promise of enjoying the Lord forever, lost initially with Adam’s sin in Eden and which the Lord would eventually restore through the Seed of Eve prophesied in Genesis 3:15.

The total destruction of Canaan fits into this in a practical way. Had Israel followed the Lord’s commands, the nation would have had internal religious unity. Such a unity, grounded in God’s law, would have had significant geopolitical implications. Geographically, Israel straddled the primary north-south/east-west trade and invasion routes of the ancient Near East. East of the river systems feeding into the Jordan River, the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea, the topography of the Near East becomes desert. Thus, a unified Israel, faithful to her Lord would have been the lynchpin of the region—everyone would need to pass through the country to conduct trade in the region. At the same time, no one could invade without enlisting Israel’s support or tacit acceptance. By refusing alliances, Israel could have been an enforcer of the peace. The social and cultural influence of the Lord’s Israelite Kingdom would have emanated out to the known world. As it turned out in Israel’s actual history, the failure to rid the land of pagan influence did eventually become a snare that left the nation internally divided and ultimately led to its undoing. The only time Israel even approximated the influence it could have had if it had been faithful to the Lord was under Solomon’s reign. Indeed, Solomon’s forty-year reign (971-931 bc) was the only time in the nearly 1,000 year period covered by the Old Testament that the nation was internally united and free from external threats. Second Chronicles chapters 8 and 9 describe the country as rich from trade, militarily significant, and chief among—and arguably a suzerain over—its neighbors. Solomon’s wisdom from the Lord attracted people from far away, notably the Queen of Sheba. However, Israel’s failure to eradicate Canaanite influence and Solomon’s willingness to indulge in pagan practices as part of his many marriages would eventually lead to the destruction of the entire nation. As the Lord had judged the Canaanites for their sins, so too would He judge Israel for engaging in the same practices that so dishonored Him. The Lord was consistent in his enmity towards those things that desecrated His image.

If the conquest of Canaan anticipated the eschatological rest for the People of God, then judgment upon Canaan, harsh as it may seem, also anticipates God’s eschatological judgment on the world. This only stands to reason. As noted earlier, the Angel of the Lord mentioned in connection with the holy war passages in Exodus 23 and Deuteronomy 20 is likely to have been the pre-incarnate Christ. Christ also, of course, is the slain Lamb in Revelation chapter 5 who approaches the throne of God and is able to open the seals of judgment. Against Him the kings of the world will wage war (Rev. 17:14) and He will defeat them, leading the armies of Heaven, executing the wrath of God, and establishing His suzerainty (Rev. 19:11-19). The Final Judgment, coming at the time of Christ’s return, will be total. The completeness of this judgment is manifest from the laments given by the world over the destruction of the idolatrous world system, the Harlot of Babylon. Only those written in the Lamb’s book of life will be allowed to enter into His eschatological rest (Rev. 21:27).

The Final Judgment will bring full circle the pattern of judgment that the Lord has executed since the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden. The judgment on Canaan seems harsh to modern ears because it is so bluntly explicit. In the context of Scripture, however, it is actually more moderate than God’s earlier judgment in the Flood. There God destroyed the entire world, save only Noah’s family. One also should remember that the Lord’s judgment is refined throughout Scripture. Following the Flood, in Genesis 11, the Lord disperses the nations. In the Exodus He ruined a great nation, Egypt. With the judgment on Canaan, He destroyed city states. Later, He expelled first Israel and then Judah from the Land for their covenantal disobedience. In Christ, all the world is again judged, but the full unmitigated force of God’s wrath is taken on by One only, Christ Himself. In the Final Judgment, as with the Flood, all individuals outside of the covenant community will be judged.

The refined scope of the Lord’s judgment is paralleled by the growth in God’s redeemed community. Prior to the Flood, human institutions were so nascent that they provided no effective restraints on human behavior. People really could be as bad as they wanted to be, and here it is not surprising to see the Lord’s harshest judgment. In an age when great nations dominated the international scene, God judged the preeminent empire at the time, Pharonic Egypt. In the course of that judgment, He created His own nation, Israel. At the same time, when city states were beginning to coalesce elsewhere in the ancient world, He judged the city states of Canaan in part to give His people a homeland. The destruction of Israel and Judah coincided with the growth of the ancient empires (Babylonian, Persian, Greek and ultimately Roman). That destruction dispersed God’s people throughout the known world. When Christ arrives, the international scene was unified by the Roman Empire, eventually allowing the proclamation of the Gospel to go to the ends of civilization. It is no coincidence that in this period between the ascension and return of Christ, a time of the ingathering of the nations (John 4:35), civilization has become global and God’s people are being drawn from the ends of the world. The significance of this parallelism between God’s increasingly refined judgment and the ushering in of the covenant community—and with Christ, of the Kingdom—is that in each phase of judgment God is simultaneously preparing the way for the Kingdom.

What Does This Mean for Us Today?

To pull together the various threads discussed so far into some closing thoughts, there are three questions that should be posed. First, what do these holy war passages tell us about God? Second, are they a biblical model for warfare today? And lastly, if they are not such a model, then what do they have to say about a Christian perspective on war?

In juxtaposing the judgment of the Lord with our assumptions about His loving and gracious nature, the holy war passages challenge us as Christians to think more deeply about the fact that God is not some cosmic force, but a Person and an omnipotent One at that. Understanding who God is requires both a reverential fear for the sheer power that He possesses and a humility in appreciating the complexity of His personal character. Without such an approach, the temptation would be to put God on the witness stand and set ourselves up as the judge of His character. That is both arrogant and naïve.

The destruction of the inhabitants of Canaan certainly demonstrated the Lord’s justice towards them, while simultaneously showing His grace to those who are His people. Since the Lord is our covenant suzerain, our loyalty is to Him personally, not to an abstract principle. This is all the more true since Jesus Himself was both the leader of the army of the Lord in the Old Testament as well as the Victorious One who will bring the Final Judgment at the end of time. The fact that Christ is depicted meekly in the Gospels is consistent with the Father’s purpose at that time—to reconcile to the Father those the Father gave Christ, to inaugurate the Kingdom, and to initiate the ingathering of the nations that must precede the Final Judgment. This underscores the fact that as a Person, the Lord does have an agenda and that agenda is bound up with having His image reflected through all of creation by His image bearers.

The Lord’s defense of His image is not self-centered, but an acknowledgement of His perfection and aseity. An analogy would be a company’s effort to defend its brand image. If someone outside the company were to take the brand logo and use it on their own website to make money and engage in illegal activity, the company would be fully justified in taking the individual to court in a civil suit to restore their reputation and recover damages for the injury done to them. The Lord, likewise, is justified in defending His image. A difference between the analogy and the biblical reality, however, is that the degree of harm man has done to God’s image is far greater than that by an individual hijacking a company logo. It is desecration, not just copyright infringement. On a personal level, this should deepen the seriousness with which we view our sin. The Lord judged the Israelites as well as the Canaanites. As Christians, it is this wrath Christ bore for us.

These holy war passages raise the temptation that if the Lord was so zealous to defend His name and image, should not Christians be similarly zealous and could not these passages serve as justification to do likewise. This, of course, is the temptation of the Crusades. Biblically speaking, however, the fact the Lord Himself provided that once the land was conquered the laws of war would revert to the then-prevailing international norm is sufficient evidence that this war of total destruction was never intended to be the norm. Unlike the Muslim attitude towards Allah, while God requires us to honor His name He does not require us to do it by violent means. The Lord will ultimately defend His name. The danger for making this normative for Christians today is that human nature is still corrupted by the Fall. God could execute such judgment perfectly because He is perfectly self-controlled. If we take on decisions to be “agents of God’s wrath” we risk conflating His agenda with ours.

This does not mean that the passage has no bearing on how we are to think of warfare today. In considering the Canaanite society that the Lord commanded to be destroyed, it should be a spur to us to think about justice. Canaanite society not only was desecrating the image of God, but it was also a nasty society to live in. If we are to love our neighbor as well as the Lord, then we need to be outraged at how depravity dehumanizes people and wise to how such depravity becomes embedded in social networks. The fact that the Lord authorized warfare and given the unchanging nature of His character means that warfare can be a just pursuit—a virtuous good rather than a necessary evil. As Christ was a warrior, then we, like Him, need to have our means consistent to the ends we seek to achieve and the justice we hope to establish. For us, those ends—and therefore the means for achieving them—will always be more limited. When to declare war, on what grounds, and for what ends are all issues that we would need to look elsewhere in Scripture beyond the holy war passages for answers.

Printable Version

[1] Kambanda was the Prime Minister of Rwanda during the Rwandan genocide in 1994 and was later convicted for his role in it by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.